It’s hard to design and build collaborative software. Everything is tied together, so a small change in one place has far reaching impact.

It is also extremely valuable. We’re a social species. Think back to your most memorable meals, favorite travel destinations, and biggest personal breakthroughs. Chances are all of these experiences are significant because of the people you’re sharing them with. Our digital lives are the same.

This brief essay illuminates the process of crafting a collaborative writing experience for Minimal. It should be useful for designers, engineers, and anyone interested in how things come together.

Enjoy.

Cloud Sync

Before setting out to build collaborative notes, Minimal already had a robust Cloud Sync system in place. As a writer made changes on their iPhone, they could trivially pick up where they left off on an iPad or Mac without any hurdle. It’s seamless, and it's fairly close to what I wanted to accomplish for multiple writers.

Since many writers use this app on airplane mode or in places with poor internet connection, it is critical that the app on the writer's device also function as a source of truth and continuously resolve conflict with what is stored in the cloud. These early requirements turned out to be a great advantage: they forced me to craft a robust system that could handle difficult and confusing sync events.*

Fortunately, the code for Cloud Sync was well-composed. Since it was descriptive and abstract, it was possible to build collaboration directly on top of this personal Cloud Sync layer while few architectural changes.

Reading through Apple’s CloudKit documentation, I learned that we needed to support multiple databases (both a private database and a shared database), and multiple record zones and record types – one type to embody the shared properties of a note, and another to embody personal properties of a note that sync only for the individual.†

I dedicated about two days to simplifying and abstracting the code, massaging Cloud Sync into a content-agnostic sync engine that could handle any data type, and any number of participants. The code became smaller, more readable, and more powerful.

A useful metaphor might be found in kitchen utensils. Instead of having a unique tool for every task, most of the things in our kitchen can handle multiple jobs. Our pot can boil water for pasta, or produce soup. A paring knife can both stir a Negroni and slice the orange peel that we will use as garnish. When we extended the Cloud Sync layer to support collaborative writing, we cleaned out and simplified our metaphorical kitchen equipment, leading to fewer functions that could accomplish more.

Simultaneous Edit

Addressing conflict when multiple people make changes at the same time is by far the hardest problem to solve. There are two avenues of solutions: providing feedback to writers as their notes evolve, and harmoniously resolving conflict so that multiple people can write at once.

Resolve Conflict

In gist, this is how conflict resolution works. It all takes place on the writers' devices – not in the cloud.

As a note evolves, we keep a simple version history. Specifically, we observe the last ubiquitously synced expression (the version of the note that landed on the cloud and presumably went out to all other devices, or will soon go out to all other devices), the most recent expression on our device, and the proposed expression coming in through the cloud.

Then we use the longest common subsequence to create a story of changes or a “diff story” to describe how the note is evolving.

Here’s the most common conflict:

Imagine Person-A inserts “123” and then gets a sync event from Person-B. For Person-A, it looks like Person-B deleted “123.” With the story of changes, however, we know that in fact Person-B’s sync landed for Person-A before Person-B received Person-A’s insertion of “123.” Referring to our story of changes, we know that we should keep the “123,” invalidating Person-B’s purported deletion, and move on.

The problem described above is the most common conflict. There are others, and the longest common subsequence and the “story of changes” that it powers offers the solution for every conflict I could identify. It’s powerful.

This story-of-changes approach to finding truthfulness in a collaborative space is similar to the technique anthropologists use to define a culture’s belief system. I understand Anthropologists watch a culture evolve, and pay particular attention to deviations. These deviations and the responses they solicit illuminate the edges of a culture, helping to define its characteristics. Without contrast, it's difficult to observe anything clearly.

Writer Feedback

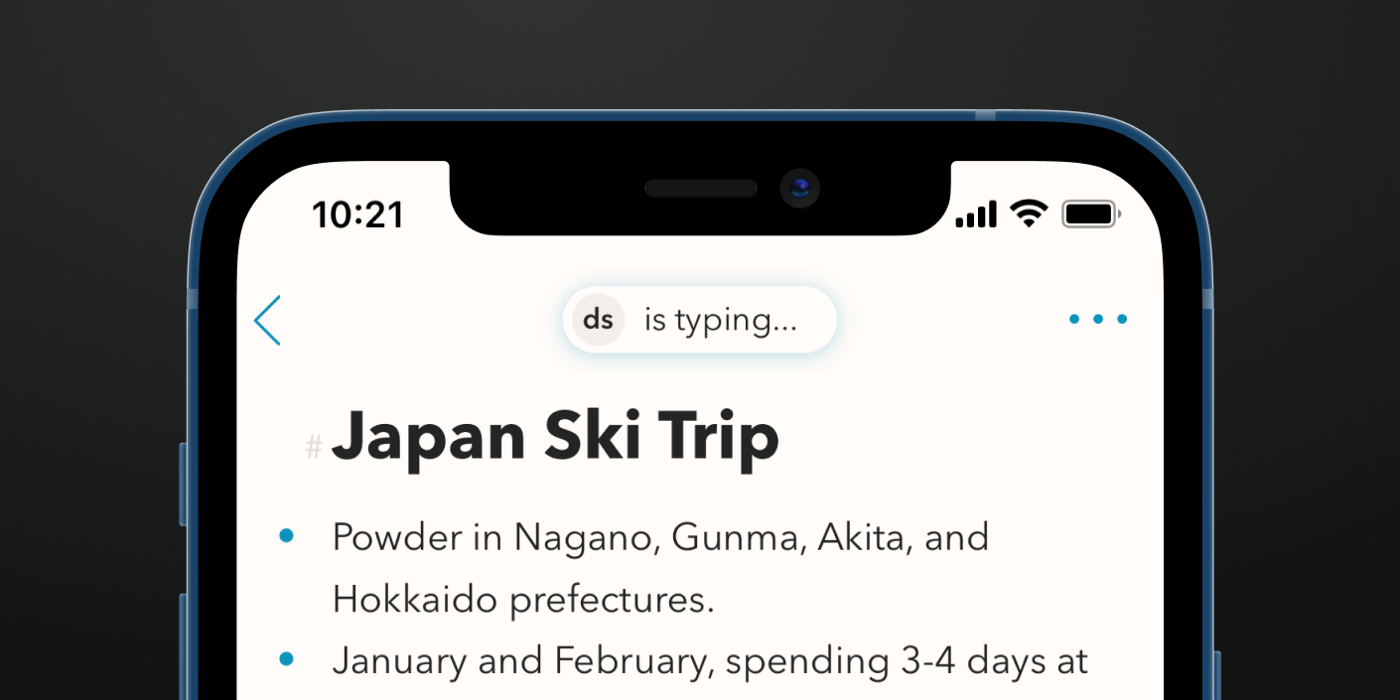

For feedback and clarity, I placed a banner at the top of the screen to indicate the state of the collaboration.

Most of the time, this banner clarifies if a note is collaborative and visible to other people. I think of this as a security feature, or a warning that the note is a shared space.

When someone starts typing, the banner glows and gently pulses, letting the writer know someone is actively working in the space with them.

Typically in software products this kind of banner appears and then disappears to let people know of state changes. For example, connecting to Bluetooth devices on the iPhone or iPad throws a pill-shaped banner that goes away after about 3 seconds. What we’re doing here with a persistent pill-shaped banner is a bit of a violation of standards, but it provides such useful information that I believe the deviation is worth it.

Incoming Sync

As sync events arrive, we show the change landing with a beautiful fading rectangle around the new text. The rectangle gradually fades away, creating a wave-like pattern. Writers watch their collaboration take shape.

Invite Collaborators

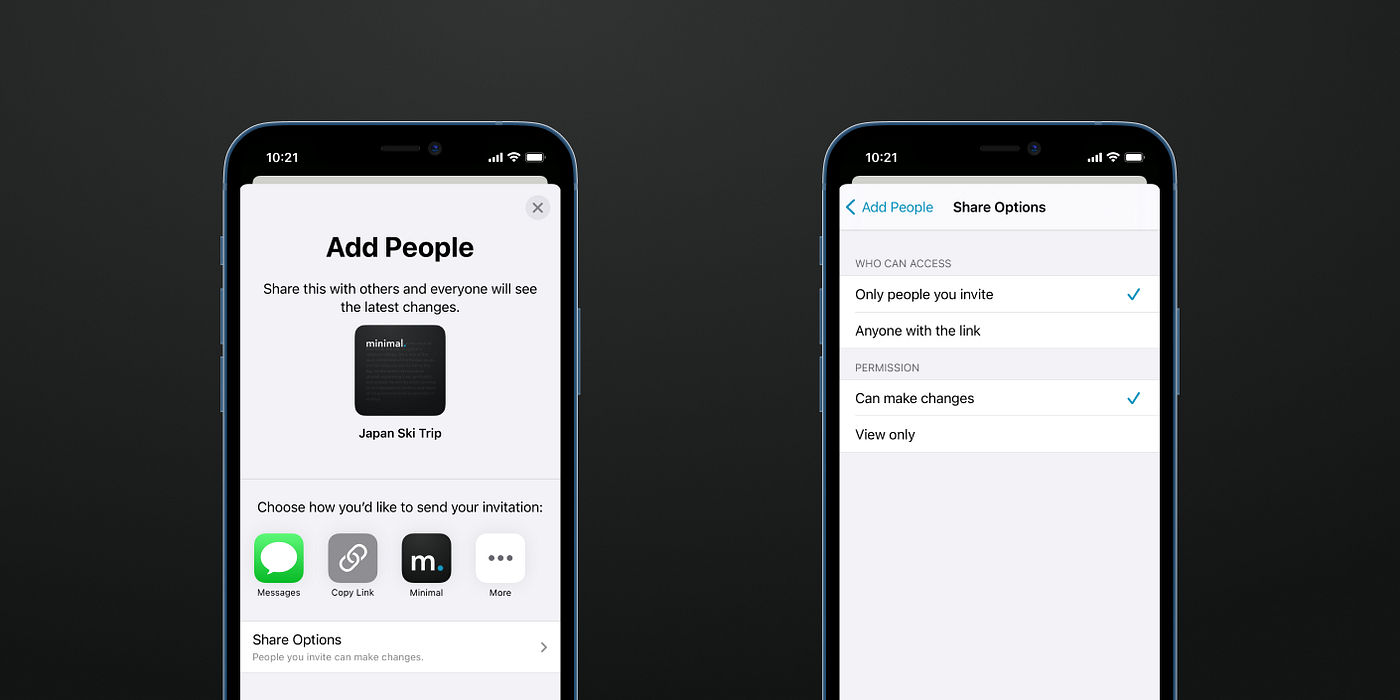

For inviting collaborators, I decided to use Apple's cloud sharing controller. It readily handles most of the edge cases (and there are a lot of edge cases!), allowing writers to start inviting collaborators with the least amount of custom code and custom interactions. This approach also provides a familiar interface, allowing people to adopt the new feature with relative ease.

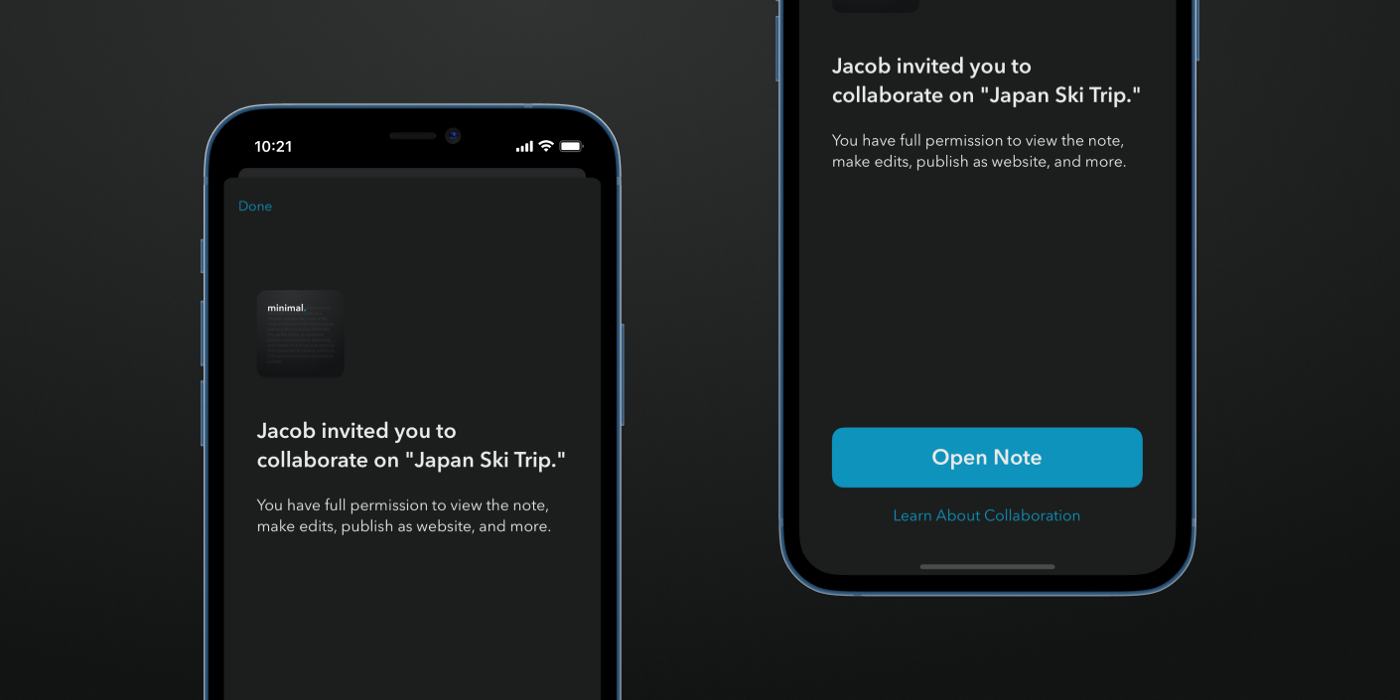

I added a note title, a descriptive sharing image, and a fallback url for new writers who have not yet installed Minimal. I also crafted this contextual invite success message as writers join new collaborations.

It’s a delightful experience. If my brother invited me to plan a ski trip to Japan in a collaborative note, you bet I’d download that app right away, and I’d probably even start a paid subscription.

Real Impact

Collaborative writing multiplies Minimal’s value, similar to how a meal tastes better in the company of loved ones. As a gardener might describe it, it’s not the parts that matter — it’s the relationships between parts that define a system and bring it to life.

🌲

* The gist of the Cloud Sync architecture includes local Note storage, out-going syncs to Apple's CloudKit servers, in-coming syncs from the CloudKit servers, and layers of conflict mediation in between that occur on-device. The CloudKit server notifies the app when a change has been made, and the app then queries the server even if it is in the background. As writers make changes to their notes, these changes are pushed to the server and relevant local Note objects are marked as successfully synced. If a note fails to reach the server, sync will be re-attempted again later.

† Some note properties should be unique to the individual writer, including archive and pin statuses. Other note properties should be ubiquitous for all participants, including last-edit-date and the note's body text. For privacy purposes and architectural clarity, these two types of note properties are stored on separate records in separate databases.